Rascals case in brief

In the beginning, in 1989, more than 90 children at the Little Rascals Day Care Center in Edenton, North Carolina, accused a total of 20 adults with 429 instances of sexual abuse over a three-year period. It may have all begun with one parent’s complaint about punishment given her child.

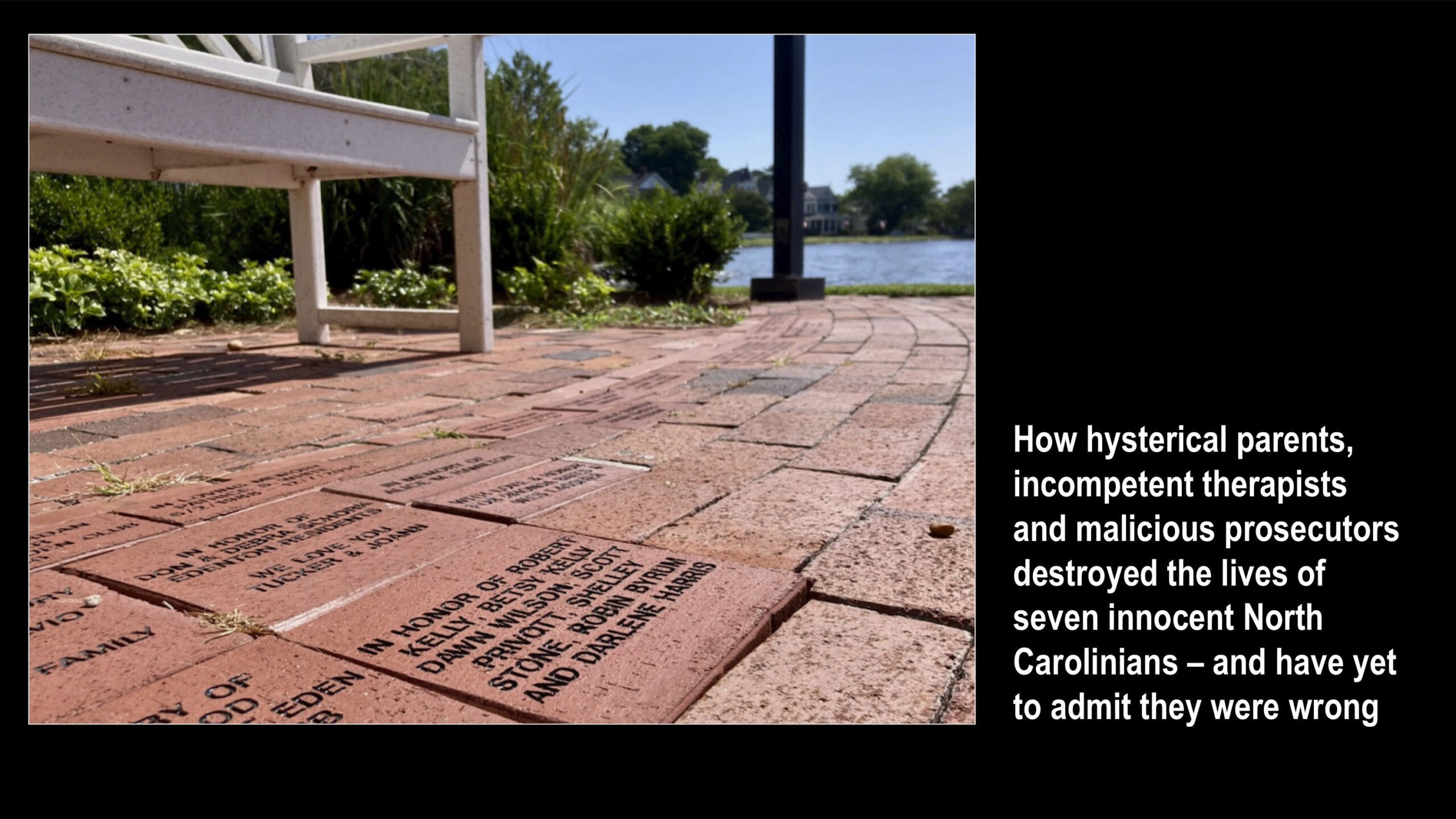

Among the alleged perpetrators: the sheriff and mayor. But prosecutors would charge only Robin Byrum, Darlene Harris, Elizabeth “Betsy” Kelly, Robert “Bob” Kelly, Willard Scott Privott, Shelley Stone and Dawn Wilson – the Edenton 7.

Along with sodomy and beatings, allegations included a baby killed with a handgun, a child being hung upside down from a tree and being set on fire and countless other fantastic incidents involving spaceships, hot air balloons, pirate ships and trained sharks.

By the time prosecutors dropped the last charges in 1997, Little Rascals had become North Carolina’s longest and most costly criminal trial. Prosecutors kept defendants jailed in hopes at least one would turn against their supposed co-conspirators. Remarkably, none did. Another shameful record: Five defendants had to wait longer to face their accusers in court than anyone else in North Carolina history.

Between 1991 and 1997, Ofra Bikel produced three extraordinary episodes on the Little Rascals case for the PBS series “Frontline.” Although “Innocence Lost” did not deter prosecutors, it exposed their tactics and fostered nationwide skepticism and dismay.

With each passing year, the absurdity of the Little Rascals charges has become more obvious. But no admission of error has ever come from prosecutors, police, interviewers or parents. This site is devoted to the issues raised by this case.

On Facebook

Click for earlier Facebook posts archived on this site

Click to go to

Today’s random selection from the Little Rascals Day Care archives….

Click for earlier Facebook posts archived on this site

Click to go to

Today’s random selection from the Little Rascals Day Care archives….

Prosecutors’ bag held one last trick

May 10, 2013

“Evidence at the trial of Robert F. Kelly Jr. consisted mainly of the fantasy-laced testimony of children and no physical proof. His conviction was overturned by an appeals court that said the proceedings had been unfair. Now prosecutors have dug into their bag of tricks and, ta-dum, come up with a new set of sex-abuse charges against him.

“It may turn out that Nancy Lamb has better documentation for the latest accusations, which date to 1987 and involve a girl who was then 9. She better have. Otherwise, the public will be left to conclude that the prosecution is simply engaged in a malicious effort to save face.”

– From “Never-ending prosecution” (News & Observer editorial, May 7, 1996)

Unable to gin up such documentation, of course, Lamb finally dropped the new charges – 2½ years later! And the public was indeed left to conclude that they had all been “a malicious effort to save face.”

‘Attached to their convictions’ – and then some

Dec. 24, 2012

Dec. 24, 2012

“Why prosecutors sometimes fight post-conviction evidence so adamantly depends on each case. Some legitimately believe the new evidence is not exonerating.

“But legal scholars looking at the issue suggest that prosecutors’ concerns about their political future and a culture that values winning over justice also come into play. ‘They are attached to their convictions,’ (says Brandon Garrett, a law professor at the University of Virginia), ‘and they don’t want to see their work called into question.’ ”

– From “The Prosecution’s Case Against DNA” in the New York Times Sunday Magazine (Nov. 25, 2011)

“Attached to their convictions,” indeed. Nancy Lamb was so attached that in 1996, after Bob Kelly’s 99-count conviction was overturned, she rummaged around the office and turned up yet another molestation claim – this one from two years before the Little Rascals arrests.

Gerald Beaver, Kelly’s attorney, pointed out that the law requires any report of sexual abuse to be investigated immediately and called police investigator Brenda Toppin, who testified that she had told Lamb about the claim in 1992. Lamb denied any recollection of Toppin’s comment.

“All of this ‘We care about the children’ kind of went down the drain after the conviction,” Beaver said. “It was only when (Kelly) successfully appealed and was no longer pulling 12 consecutive life sentences that the state felt compelled to go out and find this witness.”

As usual, however, time proved no object for prosecutors dedicated to making life miserable for Little Rascals defendants. It would be 1999 before they dropped the final charge against Bob Kelly.

Was there nothing to fear but ‘day care itself’?

April 19, 2013

“What can have spurred so many communities to such (ritual abuse) hysteria? The answer may be day care itself. The mothers who report that children never lie are simply unfamiliar with the ways of children. They may also feel guilty about putting their children in day care. A righteous rage against the day-care provider can certainly distract a parent from wondering whether she is doing an adequate job as a mother.”

– From “Believe the children?” by syndicated columnist Mona Charen (October 11, 2003)

Although Charen approaches the subject as a proselytizer for stay-at-home motherhood, less partisan observers also have speculated about the role of day-care guilt.

Seeking corroboration isn’t disrespectful – it’s useful

Dec. 10, 2014

Dec. 10, 2014

“More than a decade ago, I wrote about the McMartin preschool case, and other satanic ritual child abuse accusations that turned out to be false. Back then, the slogan many supporters of the accusations brandished was, ‘Believe the Children.’ It was an antidote to skepticism about real claims of child abuse, just as today, ‘Believe the Victims’ is a reaction to a long history of callous oversight of rape accusations.

“ ‘Believe the Victims’ makes sense as a starting presumption, but a presumption of belief should never preclude questions. It’s not wrong or disrespectful for reporters to ask for corroboration, or for editors to insist on it. Truth-seeking won’t undermine efforts to prevent campus sexual assault and protect its victims; it should make them stronger and more effective.”

– From “Reporting on Rape” by Margaret Talbot at newyorker.com (Dec. 7)

Given the prosecution’s strategic secrecy, the pursuit of corroboration in the Little Rascals case presented an enormous challenge. But news coverage could been far more skeptical and revealing – perhaps even game-changing. The editor of the News & Observer certainly thought so.

0 CommentsComment on Facebook